About Goa Chitra Museums

Mission

Preserving the past to enrich the future

- To preserve and display traditional cultural artifacts to garner awareness and appreciation of past traditions, allowing people to become aware of their roots and take pride in their rich ancestry.

- Archiving of Goa’s cultural heritage through documents, books, photographs, handicrafts, electronic recordings, costumes, musical instruments, artifacts and oral history.

- To showcase the rich heritage of implements, tools, arts, crafts, as evidence that our ancestors were self-sufficient.

- To acquaint visitors with eco-friendly indigenous technology that maintained a balance with the natural surroundings.

- Ensuring the preservation of traditional forms of expression like music, folk dance, theatre, folklore by inspiring the younger generation to continue these art forms by exposing them to their heritage.

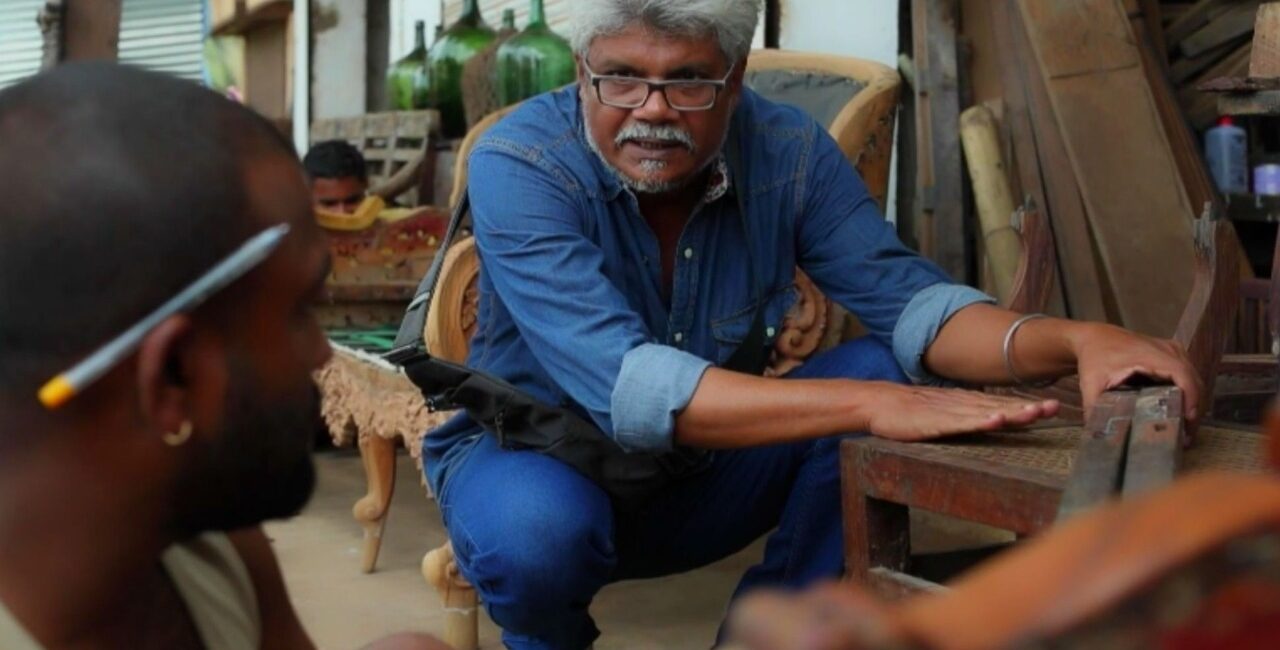

Victor Hugo Gomes

Founder & Curator

Victor Hugo Gomes dons many hats- that of an artist, musician, actor, researcher, collector, and restorer, and has single-handedly brought all of his passions under one roof with a larger purpose to preserve and share Goa’s rich culture and heritage. His fascination with the age-old traditions and tools, and the realization that it would one day be irretrievably lost has culminated into this 30-year labor of love that houses over 40,000 priceless cultural artifacts he has personally collected.

With his Lalit Kala Academy scholarship in 1992, he studied “Experimental transitions in the world of art” and returned to Goa to set up the Museum of Christian Art in Rachol. In 2009, he set up his flagship Museum- Goa Chitra, which immediately received international acclaim. Soon after, 18 European Museums extended recognition to Victor and Goa Chitra and he was offered the opportunity to display his collection of Goa’s costumes and jewellery at the University of Lisbon.

Some of the prominent awards and accolades conferred to Victor Hugo Gomes are Man of Excellence, 2021, Pride of India, Goa Edition, 2021, DKA-cho Delgado Sonvstha Puroskar, 2017, The Felga-Gracias Award, 2015, Business Goa Award, 2014, For corporate excellence in conserving Goa’s heritage and culture, The V.X. Verodiano Award (USA), 2009 - For the commitment to conserve and showcase Goa's ethnographic past for posterity's benefit and realization.

Impressed with his work, the British Council appointed him to the extensive task of mapping Museums in Western India – a project that influenced his ideas. Through his research, he concluded that the Museums needed special reform, with proper documentation and with narratives that people could connect with. This manifested in his unique style of displaying his collections at his Museums to make it a “laboratory for learning” culture, heritage and history

With his world-class exhibits and his deep knowledge on heritage, tourism, environment and more, he has often been invited as a key-note speaker at various events including ”Death of Architecture ” by IIID (2018), PFA Art Festival (2017), “Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage” by UNESCO (2015),and selected for several professional workshops organised by The Met, The British Museum and more, and has his own TED Talk and his documentary “Portrait of a Goan Collector”.

Victor’s desire to preserve the past extends beyond the material culture and extends into the “intangible culture of Goa”- the art, music, language, food and more, which he believes is gradually slipping away. His passion and appreciation for art, beauty, music and for Goa drives him to create unique experiences for visitors at workshops, exhibitions, concerts and other events.

Victor’s knowledge comes more from instinct, understanding and experiences, than from books, which is also how ancestors learned. His mission is to share their knowledge and inspire people to utilise their wisdom to enrich the future and shape a better world.